Mangroves and saltmarshes play a critical role in supporting the health of the bays by providing important ecosystem services including filtration, roosting habitats for shorebirds (including the rare orange-bellied parrot), fish nurseries and helping reduce coastal erosion.

Seagrass and rocky reefs are also important intertidal habitats in the bays, and are considered in the Seagrass and the Reefs topics respectively.

Mangroves are salt-tolerant trees that grow in the intertidal region of sheltered embayments and estuaries. Only one species, Avicennia marina, occurs in Victoria. Mangroves helps to prevent erosion, helps to filter the water and improves its quality and the plants sequester carbon.

Saltmarsh tends to occupy the area between the mangrove zone and the upper tidal limit, and is inundated during the spring tidal cycles. Port Phillip Bay and Western Port support a diverse saltmarsh flora, particularly herbs and low shrubs such as samphire, rushes and grasses to name a few.

Where mangrove and saltmarshes are located and thrive is determined by:

- coastal land and shoreline topography

- geology

- tidal cycles, and

- dynamic processes including sedimentation and water run-off.

There are a number of factors threatening these intertidal habitats in Port Phillip Bay and Western Port:

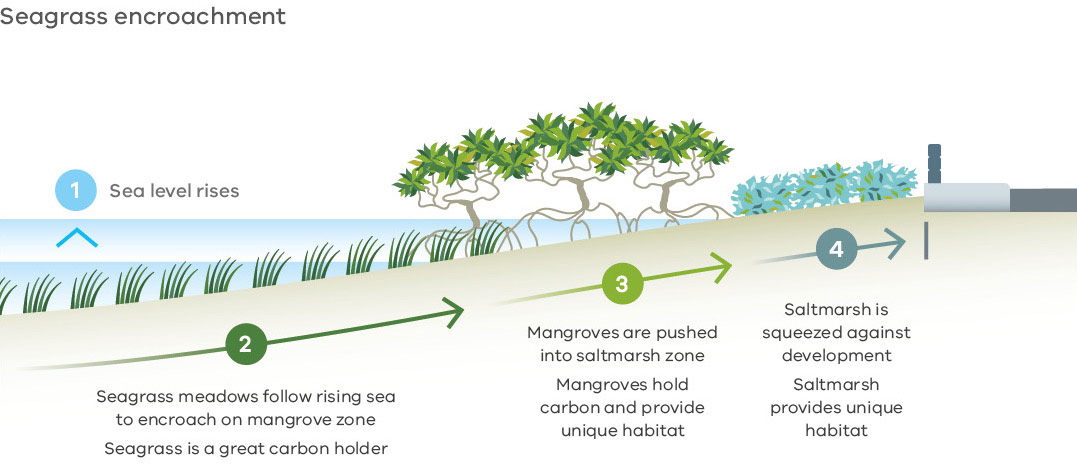

- Sea level rise is affecting mangrove encroachment (shading out saltmarsh), expanding saltmarsh pools in the north of Western Port (which fragment saltmarsh), and affecting sedimentation patterns.

- The invasive pest Spartina (cordgrass) impact on the extent and healthy ecology of intertidal habitat.

- Elevated nutrients and changes to sediment impact on the vegetation and associated ecosystems.

An estimated 30–40 species of birds inhabit the intertidal habitats of Port Phillip Bay and Western Port. These species are distributed across the habitats – some are attracted to the exposed soft sediments, others to the fresh water inputs or the open saltmarsh (like the endangered orange-bellied parrot), and others to the ponding water, both fresh and salt. Some shorebirds have salt glands and can actually drink salt water.

What happens in our estuaries has a direct impact on what happens in the bays. Contribute to the critical task of monitoring and data gathering by joining EstuaryWatch.

Estuaries are semi-enclosed bodies of water where saltwater from the sea mixes with freshwater flowing from the land. Observations, photos and water quality data collected by ‘Watchers’ are used to alert and inform marine managers of algal bloom, fish death and storm surge responses and are incorporated into estuary management plans and research projects. You can get together with like-minded volunteers once a month to conduct a variety of citizen science tasks to ensure water quality in your local area.