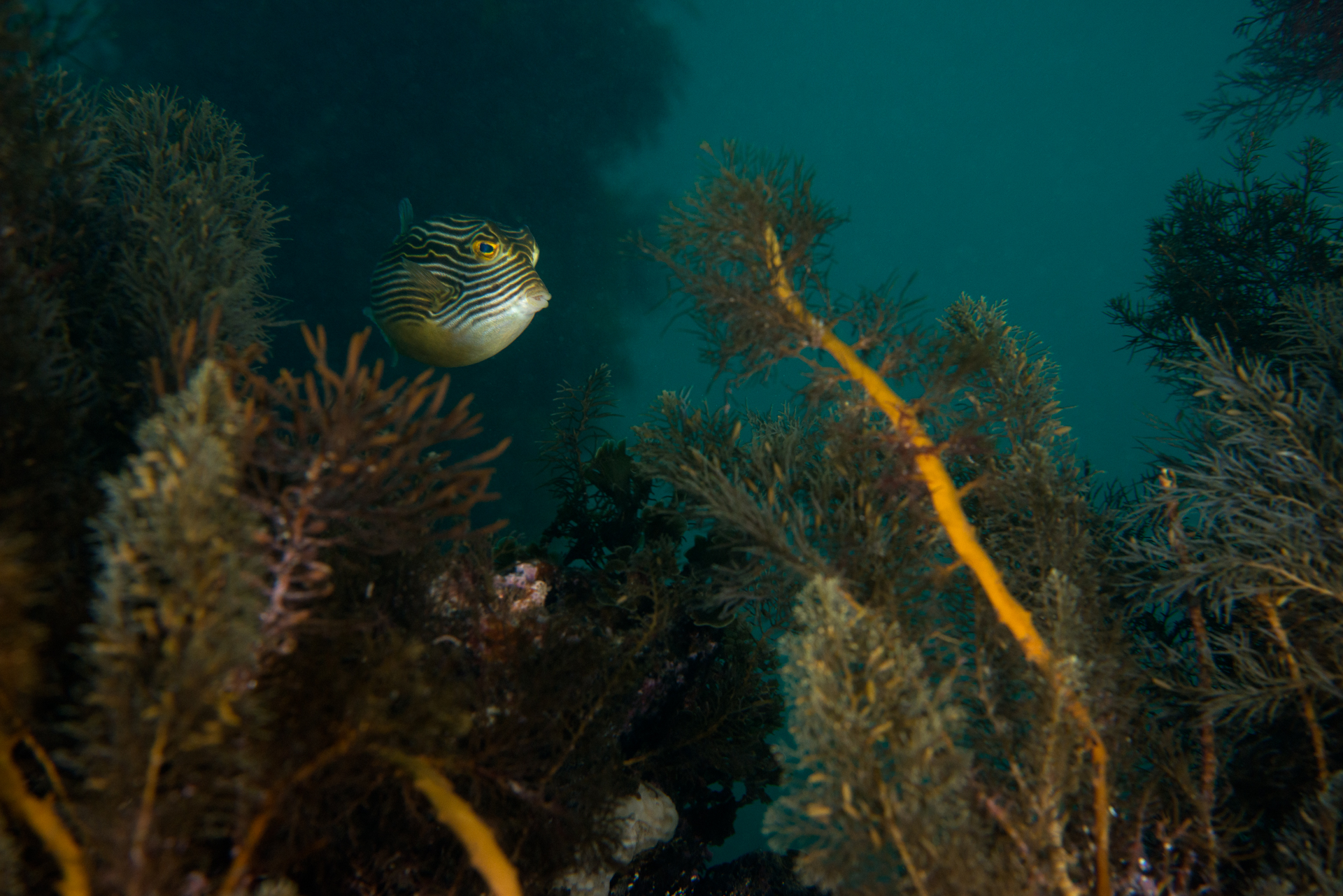

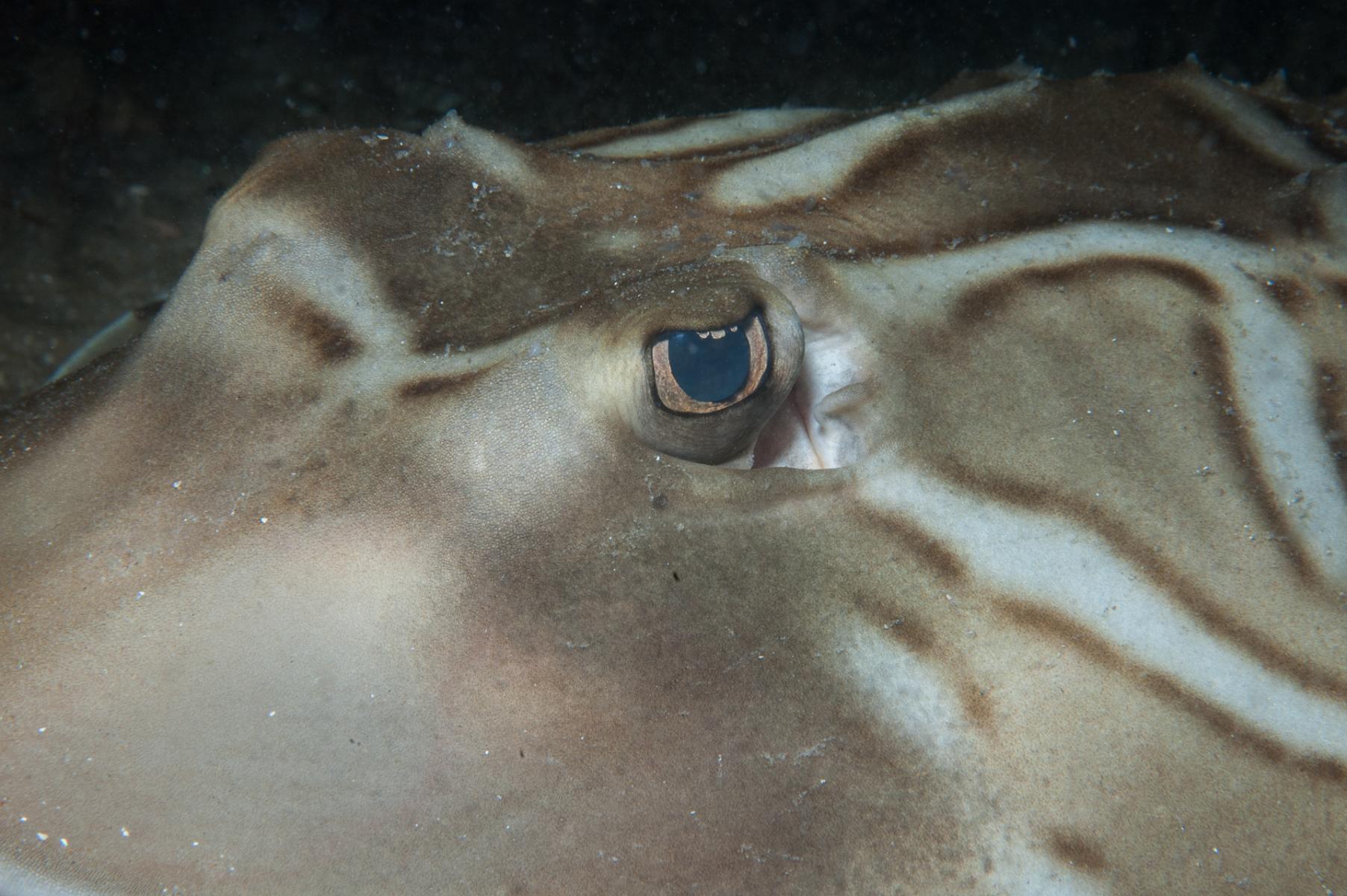

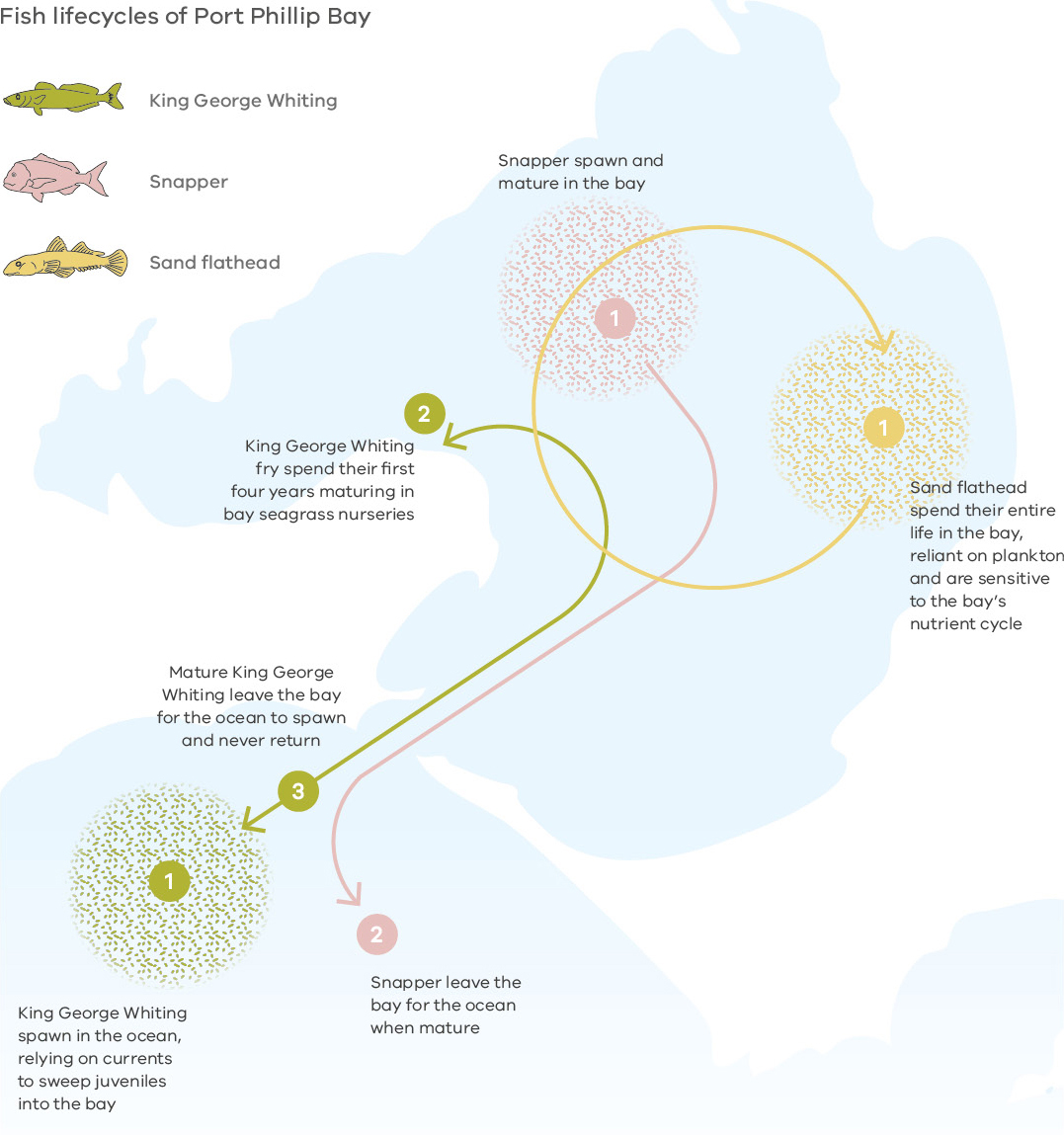

There is a high diversity of fish in the bays and they can be categorised into a range of habitats.

Reef and seagrass habitats in temperate marine waters are dominated by three particularly diverse families:

- the wrasses

- leatherjackets, and

- morwong.

There is not enough known about the impact of fishing on Western Port.

The majority of research relates to Port Phillip Bay.

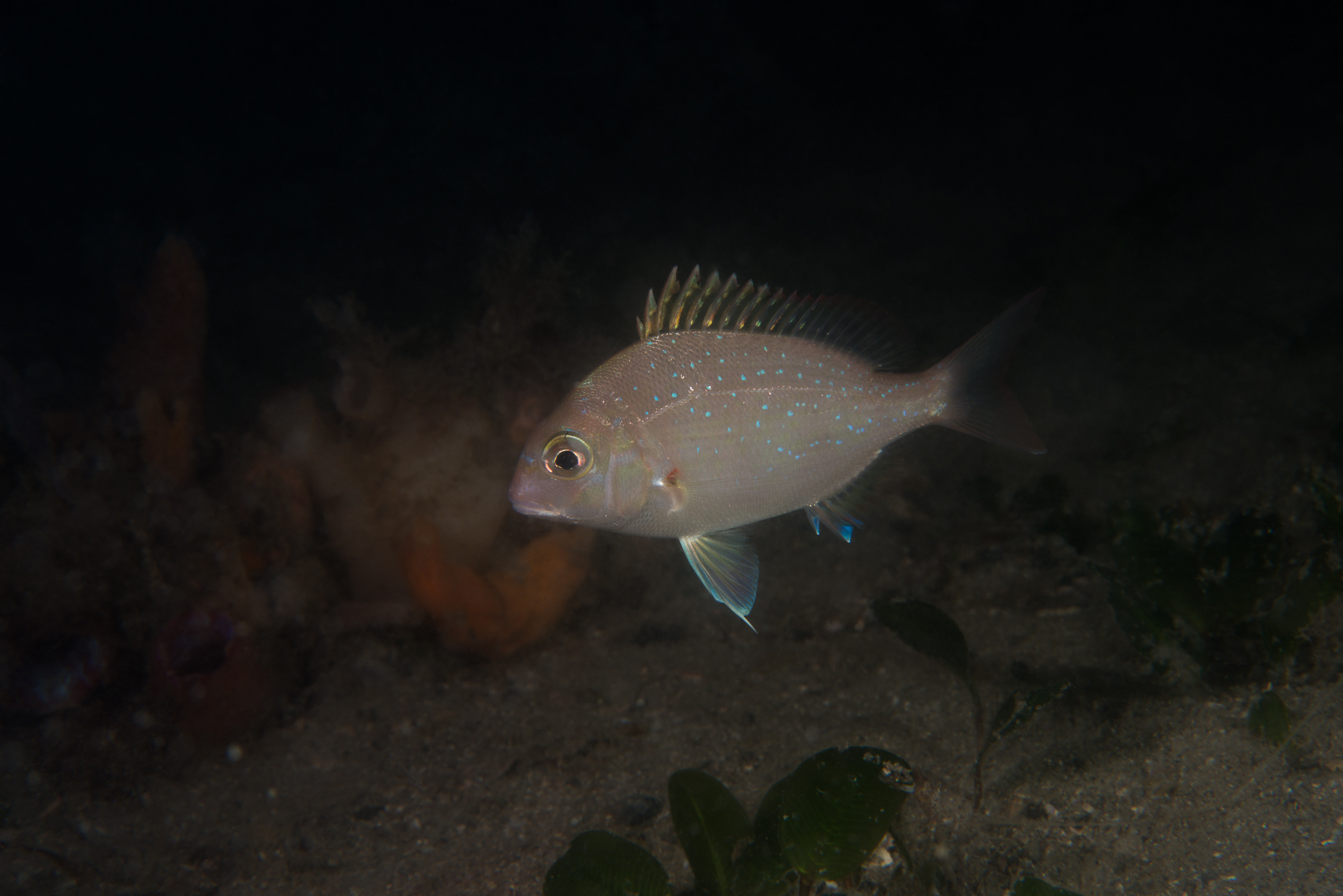

REDMAP is a way for people who live around, and visit, the coasts to share sightings of marine species that are ‘uncommon’ to the local area.

As our climate changes, so too do the movements of our fish and this makes it pretty difficult for researchers to keep track! But with the help of numerous extra eyes, scientists can follow each species to help maintain their healthy populations.